About hazard mitigation

Hazard mitigation is acting before a disaster to reduce consequences later. Mitigation involves analyzing risk, reducing risk, and insuring against risk. One example of a mitigation activity is upgrading a building to not fall during an earthquake. Hazard mitigation is the first step in the disaster cycle. Hazard mitigation is powerful and can break the expensive cycle of repetitive loss.

Mitigation usually occurs before a disaster. But mitigation is essential to the recovery process, too. After a disaster, don't aim for pre-disaster conditions, but rather include mitigation for the next disaster in the rebuilding approach. With a strong mitigation strategy, communities will be safer than before.

About hazard mitigation planning

A few federal acts formalize hazard mitigation:

- The Stafford Act of 1988: State and tribal governments must create mitigation plans after receiving federal disaster funds. States include U.S. territories, such as Puerto Rico.

- The Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000: Local governments must create Hazard Mitigation Plans to receive non-emergency disaster assistance.

- Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018: Creates more incentives and funding sources for hazard mitigation.

States, Tribal, and local governments must create Hazard Mitigation Plans to remain eligible for non-emergency disaster assistance every five years. It must be approved by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

This process is lengthy and typically takes over a year to complete. For more information and official guidance about this process, visit the FEMA website.

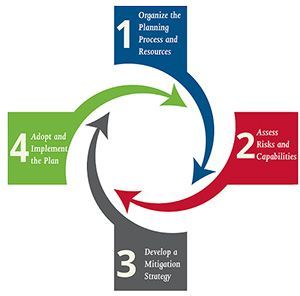

Steps to creating a Hazard Mitigation Plan that prioritizes frontline communities:

- To organize the planning process and resources, the State, Tribal, or local jurisdiction should:

- Identify and build a Hazard Mitigation Planning Team that includes many members from frontline communities. Note: Frontline communities may have challenges having trusting relationships with the government and other stakeholders due to historical injustices. Seek out community-based organizations that can help build relationships with residents. Explore using a healing-centered approach to community engagement.

- Outline a planning process that is inclusive and truly accessible to frontline communities:

- Ensure the meeting is accessible for people with limited mobility, vision, and hearing.

- Announce meetings in various publications and venues where frontline communities will see them.

- Hold meetings a variety of times so that those with alternative schedules can attend.

- Provide materials in multiple primary languages used by local frontline communities.

- Food and childcare should be provided.

- Compensate participants.

- To assess risks and capabilities, the Planning Team should:

- Partner with diverse, technical experts to understand what hazards are possible in the jurisdiction. There is an abundance of resources from regional and local governments in California, including the United States Geological Survey, the California Geological Survey, Adapting to Rising Tides, the California Office of Emergency Services, and many more.

- Seek out other resources to understand risks. For example, Native Americans believe fire is good and a culturally appropriate practice to managing wildfires -- this perspective is often missing from official sources.

- Consider lived experience and diverse voices to understand what's at risk and community capabilities. What's at risk is often dominated by wealthier communities with more expensive infrastructure. Similarly, community capabilities often do not consider the social ties and community assets that are foundational to frontline communities.

- Ensure that technical information is easy for frontline communities to read and understand.

- To develop a mitigation strategy, the Planning Team should:

- Identify and prioritize actions that invest in frontline communities. One example is using funding first to upgrade buildings for earthquakes in neighborhoods with high proportions of people of color or people with low incomes.

- Consider actions that meet the adaptation goals of the General Plan. Read more about the General Plan.

- To adopt and implement the plan, the Planning Team should:

- Develop a public comment process open to all, especially frontline communities, and organized with materials in multiple languages.

- Once the plan has completed the public approval process, the Tribal or local jurisdiction sends the plan to the State and then onto FEMA for approval. Once FEMA approves it, the local jurisdiction can adopt it through its own governing body, like the City Council. Once the plan is adopted, the jurisdiction can begin implementing it.

- Identify ways to communicate updates on the implementation process. The NYC Mitigation Plan has a great way of providing updates.

- Develop an ongoing plan maintenance and evaluation process informed by the equity vision outlined at the beginning of the process.

The benefits of having a Hazard Mitigation Plan

- It guarantees eligibility for certain types of non-emergency disaster assistance from the Federal government.

- Through the planning process, communities think about their potential risks and develop mitigation actions before a disaster occurs. This practice makes it easier to recover from future events.

- It's an opportunity for the community to come together and build social cohesion.

The funding benefit is a crucial one for local jurisdictions. FEMA currently administers four active hazard mitigation programs:

- Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP),

- Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) Program,

- HMGP Post Fire Grants, and the

- Flood Mitigation Assistance Program.

Actions to take

For community-based organizations and affordable housing providers

- Learn about the Hazard Mitigation Planning Process in your community. Reach out to the local Office of Emergency Services, Public Safety, or Planning. They are usually the agencies leading this work.

- Offer to be involved in the planning process. This chance only comes up every five years, and it's a pivotal opportunity to influence local efforts to minimize disaster risk.

- Help local governments incorporate equity into the plan by talking about the various benefits it will produce. For example:

- Investments that reduce the risk for frontline communities, reduce social service costs, and save local government future costs.

- Hazard mitigation projects that employ local hiring practices result in a more productive workforce and positively impact the local economy.

- Many investments in frontline communities can achieve co-benefits like community beautification, green space, and tree cover, reducing heat stress and heat-related illnesses.

For local government

- Build relationships with community-based organizations so that they will feel comfortable being on the Planning Team.

- Identify community organizations to be sub-applicants for BRIC funds to conduct planning and mitigation projects to reach difficult to serve populations. This process can help build local organizational capacity and community trust.

- Conduct a building code vulnerability audit and retrofit program that targets frontline communities. This approach would achieve the greatest risk reduction, as these households usually cannot retrofit without support.

- Projects funded by HMGP and BRIC must be considered cost-effective by FEMA's benefit-cost analysis model. Quantifying some goals or values like equity is less common and straightforward. To prioritize equity in the project benefit-cost analysis, local governments need to:

- Use non-market evaluation techniques to conduct the benefit-cost analysis. These may include air quality, tree cover, walkability, and access to green and open space.

- Emphasize local workforce development and ongoing job training opportunities through hazard mitigation investments, rather than only emphasize job creation.

- Quantify the disproportionate benefits that investments in frontline communities yield. For example, determine the risk reduction benefit for mitigating a rental property for low-income renters or low-income homeowners over a more general retrofit program.

- Identify metrics that can be proxies for equity. For example, use a policy that requires that a percentage of hazard mitigation investments serve census tracts or blocks with high Cal EnviroScreen

For philanthropy

- Offer grants to pay frontline communities for their participation in the Planning Team.

- Lower capacity jurisdictions often do not have enough resources to do hazard mitigation planning, and funding is critical to supporting this work.

- Join the planning process and support the perspective of frontline communities and offer how philanthropy can partner in the effort.

Other helpful resources

- The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Region IX produced the Level Up Audio Project to share stories, case studies, and best practices to inspire hazard mitigation action and strengthen the community of hazard mitigation and climate adaptation professionals.

- Guide to expanding mitigation: making the connection to equity from FEMA.

- The Guidebook for FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grants: Promoting Nature-Based Mitigation Through FEMA Mitigation Grants. Includes an overview of mitigation funding, helpful application tips, and case studies.

Image Sources:

City of Boston

FEMA

- Training